Autism and Food Aversion: Top 8 Tips from a Dietitian

If you have an autistic child, you’re probably familiar with eating challenges and food aversion. There are many reasons why autistic children struggle with trying new foods. Maybe you’ve been attempting food play, the division of responsibility or rewards – with zero luck. I’m here to help!

From the perspective of a dietitian, in this blog, I’ll share why children with autism are picky eaters, nutrients of concern, supplements, and diets to consider. I’ll also share eight tips to help your child learn to try new foods.

What is Food Aversion?

Food Aversion is when a specific food repulses you, so you avoid it. The aversion may be broad and cover whole food groups (i.e. meat) or different sensory properties (i.e. all ‘mushy’ or soft foods). You might have experienced this during pregnancy – I did with garlic!

In autistic children, food aversion and selective eating occur for the majority. Here’s why:

Causes of Food Aversion in Autism

Many characteristics of autism can make it challenging to eat a variety of foods, both developmental and physical.

Developmental challenges

- Limited shared interactions.

The Action Observation Network (AON) area of the brain allows for observing others’ actions, learning them, and executing them. In autistic people, this area of the brain doesn’t always function like a neurotypical brain. So, while children often model and learn to eat new foods by watching others eat, this might not work well for an autistic child.

- Rigidity of routines and a need for sameness.

The need for sameness can include the need for the same brand of food, colour, texture or smell. Your child may examine every minute detail of the food. And any small change can mean a whole new food for an autistic child!

For example, your autistic child may take one bite of an apple but refuse to eat the rest, as it has now become unrecognizable. Or a Goldfish cracker missing its tail will be set aside.

Physical challenges

Constipation

An autistic child is 2.7 times more likely to have constipation. And if you’re constipated, you might have a sore tummy. And, therefore, a decreased appetite. For more on constipation & what to do, read my blog here.

Food intolerances

Neurodiverse people have increased rates of food intolerances. A meta-analysis (review of many studies) with over 400,000 subjects found autistic people were 2.8 times more likely to have food sensitivity.

If you notice signs of allergy, ask your doctor for a referral to an allergist. Here are some allergy signs to watch for.

Muscle Motor Challenges

One study reported decreased muscle tone (hypotonia) in 51% of ASD children. So, having the correct posture and a supportive chair with a foot rest at the table is especially important to help stability.

Gross and fine motor skills can also be delayed, and they are essential for eating skills. The therapists working with your child need to consider your child’s developmental age vs. chronological age when assessing gross motor, fine motor, and oral motor skills. Sometimes our expectations are too high!

Sensory Processing Issues

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input is typical in autistic people. We have eight senses, and eating involves using all of them. So, sensory sensitivity can make remaining calm when presented with new foods difficult.

Here is how a few of the senses can be affected in autism:

Auditory differences:

Autistic people can have decreased brain activation for the perception of language and increased activation for the perception of songs. We can use this to our advantage, especially in food play, with singing!

Visual differences:

A review study found that autistic children over-rely on visual input to understand and complete tasks and that brain processing of faces is different. So, instead of looking at you when teaching a child, encourage your child to look at the object.

Tactile differences:

If you have an autistic child, you probably don’t need a study to tell you that they often have a more significant response or ‘overreaction’ to unpleasant textures. Tactile sensory differences don’t just relate to eating. The feeling of clothing can frequently be a struggle, too.

Additional reasons for selective eating

Some other underlying reasons of medical issues for picky eating that you might want to consider include:

- pain while eating due to acid reflux or dental cavities.

- low blood iron levels can lead to low appetite,

- breathing difficulties (due to enlarged tonsils, for example).

Depending on your concerns, you must seek support from a doctor, occupational therapist or specialist (e.g., a dentist or airway-centric orthodontist).

So, taking ALL of this into account, it’s no wonder many children with autism struggle so much to have a balanced diet. This lack of food choices can lead to a low intake of certain nutrients.

Nutritional Deficiencies in Autism

There are many reasons why autistic children (and adults, too) may experience nutrient deficiencies. Including a restricted diet due to selective eating or being on a ‘special diet.’ Or possibly malabsorption or poor digestion due to food allergies or poor methylation.

What is methylation?

MethyleneTetraHydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) is an enzyme needed for methlyation pathways in our body.

Methylation is a process of adding or donating a “methyl group” from one substance in the body to another. If one of the MTHFR genes is mutated, the person will have trouble with methylation.

Autistic people are about 1.5 times more likely to have an MTHFR gene mutation. The mutation may affect their ability to use B vitamins (especially folate and B12) and have healthy neurotransmitter and DNA synthesis.

What should you do about this? Tests such as Nutrigenomix can determine if you have a gene mutation. Or if you’re unsure if your child has an MTHFR Gene Mutation, you could just assume they do.

In that case, our body can absorb activated forms of B vitamins, which don’t require methylation in our body. Look for a multivitamin with active forms of folic acid, called l-methylfolate and other active B vitamins. Some examples include:

– Smarty Pants Gummy: (affiliate link – if you purchase from this link, your price will not change but I’ll earn a small commission.)

– Simple Spectrum powder or lollipops.

Supplements for Autism

One meta-analysis found that autistic children have lower intakes of:

- protein

- calcium

- phosphorus

- vitamin D

- B vitamins

- omega 3.

An easy way to fill some of these essential nutrients is with supplements.

The Autism Research Institute has surveyed 26,000 parents for decades who completed an online questionnaire about specific treatments and rated on a scale with “made worse,” “no effect,” or “made better.”

When deciding what supplements to offer to your child, I recommend consulting a dietitian for a diet analysis. They can recommend specific foods or supplements to help fill the gaps, such as multivitamins, calcium, vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, or probiotics.

Thankfully, supplements come in many forms, such as liquid, gummy, powder, and chewable, so hopefully, you can find one your child will take. Here’s a link to my Fullscript store with some of my favourites. Of course you can find many of these in your local grocery or health food store too.

Should I try a special diet for autism and food aversion?

If you Google ‘diet for autism,’ you might find the Feingold Diet, GAPS diet, Namecheck Protocol, dye-free diet, and gluten-free, casein-free diet.

I have a few problems with these diets:

- They add increased pressure on parents. And the kids.

- They further limit food options. And assume that the child has a wide enough variety in their diet to exclude often large numbers of foods or whole food groups.

- They won’t “cure” autism.

- The diets assume that the caregivers can access these food options and afford the added cost.

- They have limited evidence.

The dye-free diet is the only one mentioned above with decent evidence. There may be a correlation between yellow dye and sleep disturbances (which are common in autistic children). There is likely a link between food dyes and hyperactivity in kids, too.

The dye-free diet may be worth a try if your child currently eats enough foods that do NOT contain artificial dyes to try removing foods that contain dyes. Dyes will be listed on the ingredient list. Especially if you think there may be a link between these dyes and your child’s behaviour. I’d forget about the others.

But what about the Gluten-free/Casein-free diet for autism?

This diet is by far the most common diet suggested for kids with autism, so I wanted to dig into it a bit more. Thankfully, there are lots of studies on the Gluten-free/Casein-free (GFCF) diet for kids with autism.

In one study, researchers recruited 37 children and adolescents with autism. Each child consumed a standard diet (including gluten and casein) for six months and a GFCF diet for another six months. The participants were evaluated at the beginning of the study and after each diet, including questionnaires regarding behaviour. The results found no significant behavioural changes after the GFCF diet.

A 2020 review searched for randomized controlled trials on autism and the GF/CF diet, including nine studies with 521 participants aged 2 to 18 years old. Four of these studies did not significantly improve autism ‘symptoms.’ The remaining five studies showed improvement in communication, stereotyped movements, aggressiveness, language, hyperactivity, tantrums, and signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder compared to the control group. Most of the studies are poorly designed and the authors concluded: “Hence, the data remains insufficient to support the use of GCFD to improve the symptoms of ASD in children.”

This quote from another review study of the GFCF diet sums up what most health professionals and organizations believe about the diet today:

“Most investigations assessing the efficacy of a gluten-free and casein-free diet in treating autism are seriously flawed. The evidence to support the therapeutic value of this diet is limited and weak. A gluten-free and casein-free diet should only be administered if an allergy or intolerance to nutritional gluten or casein is diagnosed.”

Are you still interested in trying the GFCF diet?

First, consider whether it is too restrictive for your child. If your child survives on bread and dairy, what will they eat if you remove those? If they eat a decent amount of GFCF foods, I would encourage an allergy test first—and by a real allergist, not a naturopathic IgG test.

Of course, if your child has an allergy, removing the allergen will improve how they feel and, therefore, their behaviour. Perhaps they are sensitive to gluten or dairy and not both. Knowing this first could allow more foods into your child’s diet.

Behavioural Treatments for autism and eating

What does the research say about effective interventions to expand food selection for people with autism?

A 2019 systematic review of 36 studies, including 317 children and adults aged 2 to 22, assessed the effectiveness of interventions to increase the acceptance of new foods among people with developmental disorders (primarily autism).

‘Escape extinction,’ including ‘non-removal of the spoon,’ effectively increased acceptance of bites and prevented avoidance of target foods. However, the authors indicated other methods should be attempted before these methods “due to ethical reasons and possible negative side-effects.”

Escape extinction may be one method used in Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA) therapy, which is often used for autistic children. I don’t support ABA methods like escape extinction. Is forcing a child to eat in a therapy session a “success?” I don’t think so.

Not only will it likely damage their relationship with food (and the adult force-feeding them!), but it likely won’t translate to choosing to eat these foods at home anyway. Honestly, I’d rather a child be tube-fed than force-fed by mouth.

The study found some ineffective environmental interventions, such as physical and verbal prompts and demonstrating behaviour. It makes sense why these strategies don’t work, as we have learned that children with autism may not be able to model very well.

The review study also found that gradual exposure via systematic desensitization increased the intake of new and disliked foods. One method of systematic desensitization is the Sequential Oral Sensory feeding model (food play!), which I’ll discuss more below!

But first….

Does the Division of Responsibility work with autistic children?

The Division of Responsibility is the cornerstone for feeding kids and decreasing picky eating. As for whether the DOR “works” for autistic children – if your idea of ‘work’ is that your child eats the entire family meals…then maybe not. They may eventually learn to try new foods, but there’s no timeline.

However, following the DOR has other benefits, such as more peaceful mealtimes, fewer fights over food, and a healthy relationship with food.

If you’re unfamiliar with Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding, there are roles in feeding for the caregiver and eating for the child. Below, I’ll share how the DOR can work for an autistic child, with some possible modifications:

Child’s Division of Responsibility Roles

If/how much they eat

The child always decides how much of the foods offered at the scheduled mealtimes they want to eat. I would not alter this for any child. Coercing a child to eat only backfires.

Caregiver’s Division of Responsibility Roles:

Where food is served

Ideally, children should eat at the family table in a supportive chair (including a footrest). This chair is essential, especially for children with muscle motor control challenges.

Other modifications may be needed to make the eating setting more manageable if your child has sensory sensitivities. For example, they might need to wear headphones if they are noise-sensitive. You could also play relaxing music in the background, like binaural beats.

Remember that you might have to be flexible and deviate from the DOR for neurodiverse children. If your child only eats alone because eating at the family table is sensory overload or can only focus in front of an iPad, that might just be what you have to do—for a while, at least.

When food is served

The timing of eating consists of scheduled meals and snacks, compared to the child helping themselves to snacks all day. Autistic children thrive on consistency and routine.

Scheduled eating times also encourage appetite in children who struggle with interoceptive awareness by assisting them to learn how their body feels when their stomach is empty or full.

If your child is on medication and only has an appetite at a particular time of day, that might be a time when you would relax this rule. Allow them to eat for the entire morning, for example, if you know they won’t eat in the last half of the day.

What food is offered

Offer at least one preferred food during a meal. Ideally, the whole family is offered the same foods, including the child’s preferred food.

Sometimes, this might need modifications for an autistic individual. If your child only eats three foods, they may not eat the family food. And maybe you don’t want to eat their puree! Adequate calories and growth are a priority.

What about expanding the diet beyond a limited repertoire? Here are some effective strategies to make it easier for the child to try new foods:

Tips to Help Autistic Kids with Food Aversion

Create a Pre-meal routine

Before a meal, give your child a 5-minute warning. Have them do a physical activity before coming to the table, like jumping on a mini trampoline, crawling through a tunnel, or walking to the table with a crab crawl.

The 5-minute warning and physical activity are beneficial because:

- It provides predictability that increases comfort when transitioning between activities.

- The physical activity, or “heavy work,” provides proprioceptive input to the muscles, which is calming.

Another great thing to work into your pre-meal routine is blowing bubbles or deep breathing before the meal. You can use a pinwheel for blowing or a straw in their drink if you don’t want to use actual bubbles. This forces deep breathing, which again has a calming factor and puts your child into a better state for being at the table, eating and perhaps being exposed to new foods.

Use a visual schedule of mealtime routines.

Visual schedules communicate what’s happening before and during the meal. Visual activity schedules can reduce challenging behaviour in autistic children and promote self-regulation and play skills in multiple settings.

Grab my free download here if you want your own copy of a visual mealtime routine schedule.

If you post a meal plan in the kitchen, your child will know what’s coming up for dinner. You can find food pictures online to add to the menu. Living Well With Autism has multiple food boards here.

Make staying at the table easier

Develop sensory coping strategies so your child is more comfortable staying at the table. For example, use a supportive chair with a footrest. You can experiment with a weighted lap pad or a wiggle pad.

Depending on your child’s sensory sensitivities, you can also make eating surroundings easier. For example, reduce clutter on and around the table if your child has visual over-responsivity. Use the same simple placemat and utensils at each meal, and dim the lights (or offer sunglasses!).

Try a divided plate or learning plate for new foods.

Some children fear contamination or food touching, leading to food refusal. If your child doesn’t have a tantrum when looking at a new food, try placing one small piece of new food on their plate in a separate section of their divided bowl.

Or place the new food on a separate “learning plate.” They don’t have to eat this unfamiliar food, but they might look at it, smell it, or poke it! These are all significant steps. But if the child becomes unregulated to be exposed to this new food at the table and skips their entire dinner, don’t bother.

Social stories break down challenging situations into understandable steps. And help kids learn what to expect and what’s expected of them in specific settings.

There is a specific way to write a social story, but generally, they contain descriptive and coaching sentences. You can read a social story written for eating here from Autism Little Learners.

Make small changes to their preferred foods.

First, note that I would only attempt to change your child’s preferred food if they have enough preferred foods to drop one and still get enough to eat. If they only eat two foods, don’t touch them! The child might refuse them in the future if you present them differently.

Many autistic children or sensory visual over-responders like their food, bowl, spoon, etc., to look the same every time they eat it. To gradually attempt changing this, make one small change to a familiar food at a time until it’s accepted.

For example:

– take food out of the original package

– change the utensils you offer

– offer the food on a different plate

– change the orientation of food on the plate

– change the shape of the food slightly (i.e. cut a chicken nugget in half).

– alter the colour of the food (i.e. add natural food colouring)

– change the temperature

– change the texture (mix in some ground oats into a pancake mix, for example)

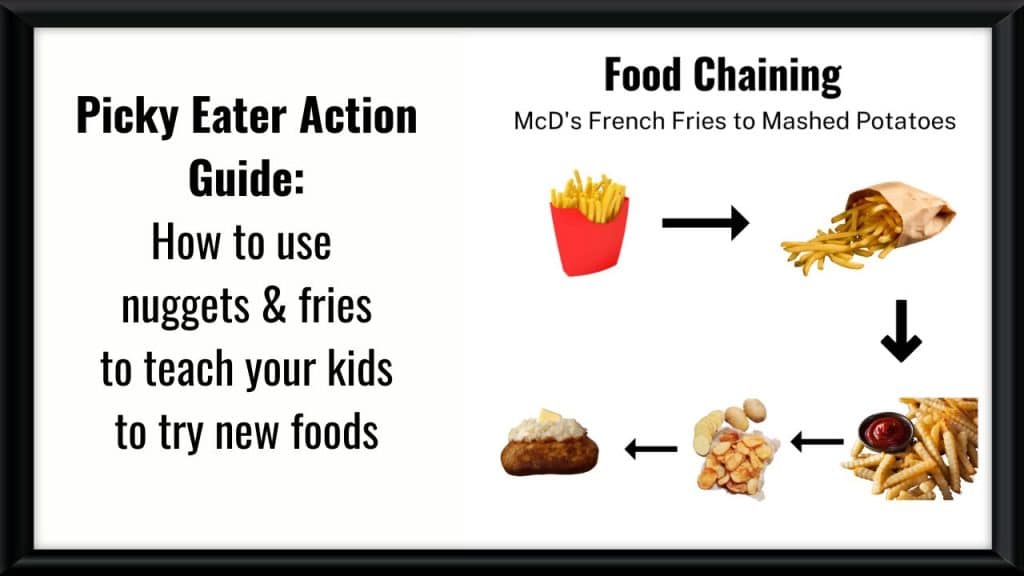

Then, you can offer a different food that changes one sensory property (i.e. different temperature or colour). This is called Food Chaining. For more information on Food Chaining and five examples, grab my freebie: “How to use nuggets and fries to teach your child to try new foods.”

Food play: Systematic desensitization.

The Sequential Oral Sensory (SOS) feeding model created by Dr Kay Toomey uses systematic desensitization for children with sensory processing disorder. It’s food ‘play with a purpose’ that gives your child positive associations to different foods’ senses, such as textures, colours, and smells.

In SOS food play, there is a 32-step hierarchy of eating, starting with tolerating being near a new food and moving on to interacting with it, touching it, smelling, tasting, and eating it. It’s not as simple for some kids just to put the food in their mouth and eat it!

Try playing with new foods away from meal and snack time. Select fun activities that appeal to your child’s interests. Do they like counting, lining up, filling and dumping, playing hide-and-seek, stacking and knocking down, or drumming?

Here are a few food play ideas:

- If your child’s favourite food is a circle shape, play with other foods in a circle shape (cucumber, Babybel cheese, salami). Rolling and wheel games would work well, too—sing wheels on the bus and roll the food around the table or up your body!

- If your child likes stick-shaped foods, make letters with them, such as pepperoni sticks, vegetables cut into a stick, or pretzels.

- If they like cube/square-shaped foods like cheese cubes, they can play with cheese and other food cubes like ham. They can line them up, stack them, or count them.

Incorporate play schemes, actions and songs during the day that you want to use later when working with food (i.e. tug of war or “The Wheels on the Bus”). Remember we learned about how people with autism can learn better by song?

Check out Dr Kay Toomey’s parent webinar for more information on the sequential oral sensory program. If your child has sensory issues, is verbal and is over age 6, you can watch my demonstration video of the SOS Food Explorer program, designed for children developmentally aged 6+.

Conclusion – Autism and food aversion

Food aversion is a common challenge for autistic children, but with understanding, patience, and the proper support, it is possible to expand your child’s food preferences!

Addressing sensory sensitivities, creating supportive routines, and creating a positive mealtime environment can help break down barriers one bite at a time.

Founder of First Step Nutrition | Registered Dietitian Nutritionist

Jen believes raising happy, well-nourished eaters who have a healthy relationship with food doesn't have to be a battle! She is an author and speaker with 18 years of experience specializing in family nutrition and helps parents teach their kids to try new foods without yelling, tricking, or bribing.

Richard Castro

Posted at 12:25h, 20 JuneThere is no known cure for autism. Treatment is based on the individual. It may include helping individuals cope with their symptoms through education and skill development, self-help, socialization and play.